Two loudspeakers, as big as the men carrying them, are brought to the rocky hilltop. Some 800m below, in the town of Hpasang, lies a sprawling Myanmar army base.

It’s a blisteringly hot day – above 40C – and behind, on bamboo poles, more young resistance fighters carry a large, heavy battery pack and amplifier. Leading the ascent is Nay Myo Zin, a former army captain who, after 12 years in the military, defected to the resistance.

With his dark green camouflage jacket draped over one shoulder, he has the air of a performer about to take the stage. He is here to urge the soldiers in the base below, who are loyal to the country’s ruling military, to switch sides.

The South East Asian nation is at a crossroads – after decades of military rule and brutal repression, ethnic groups, along with a new army of young insurgents, have brought the dictatorship to crisis point.

In the past seven months, somewhere between half and two-thirds of the country has fallen to the resistance. Tens of thousands of people have been killed, including many children, since the military seized power in a coup in 2021. Some 2.5 million have been displaced, and the military facing an unprecedented challenge to its rule and in an attempt to thwart the growing resistance regularly bombs civilians, schools and churches from its warplanes (the resistance has none).

Before Nay Myo Zin’s sound equipment is switched on, the army opens fire on his position.

Undeterred, with a flick of the switch and microphone in hand, he bellows: “Everyone, cease fire! Cease fire, please. Just listen for five minutes, 10 minutes.” Somewhat surprisingly, the barrage stops.

He tells them of the 4,000 soldiers who surrendered to the opposition in northern Shan State, and the recent insurgent drone attacks on military buildings in the country’s capital Nay Pyi Taw. The message is, we are winning, your regime is falling, it is time to give up.

Here in Hpasang and across Karenni state, across much of the country, battles and stalemates have taken hold as a great rolling rebellion threatens the rule of the military junta. The military coup in 2021 brought an end to the elected civilian government, and its leader Aung San Suu Kyi remains imprisoned, along with other political leaders.

Yet this is an under-reported conflict – with much of the world’s attention on Ukraine and the Israel-Gaza conflict. There is no press freedom, foreign journalists are rarely allowed to enter officially and when they do are heavily monitored. There is no way to hear the resistance side of this story through government approved visits.

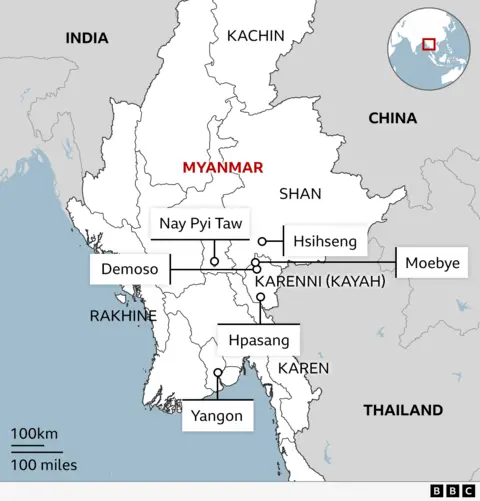

We travelled into Myanmar and spent a month in the east of the country living alongside resistance groups fighting across Karenni State, which borders Thailand, and Shan state, which borders China.

We travelled on jungle tracks and backroads, to front lines where the military has been cut off and surrounded for weeks, where like in Hpasang, the fighters have the high ground. In others, such as Moebye, further north, the opposition has suffered heavy losses as it attempted direct assaults across heavily mined ground. There, and in Loikaw, the state capital, the strength of the rebellion and its limitations are in plain view.

In Hpasang, the resistance has been playing a waiting game, confident that they have the upper hand. Some 80 soldiers have been trapped inside the base for more than a month, with about 100 more believed to be dead or injured.

Up on the hilltop, via his loudspeaker, Nay Myo Zin makes the case for surrender: “We have surrounded you. There is no possibility of a helicopter coming. Ground troops support? No. You have time today to decide whether to switch to the people’s side.”

There’s silence from the military camp below.

Nay Myo Zin urges them to abandon Min Aung Hlaing, the general in charge of the ruling junta.

“All your lives will surely be spared. This is the highest promise that I can give. So, don’t be foolish. Would you rather protect tyrant Min Aung Hlaing’s unjustifiable wealth until your last breath? Now, I am waiting to welcome you.”

Moments pass, there is only the sound of flies buzzing on the hilltop, as perhaps the junta forces are considering their response. It is no easy decision, if they surrender and are returned to military-controlled areas, they will probably be sentenced to death.

Their answer comes loudly; definitively. They again fire on the rocky outpost, the insurgents begin to duck for cover. There will be no surrender today.

Nay Myo Zin continues broadcasting, regardless. To his side, on a radio, the commander of the operation to capture the base adopts a different approach. On the same frequency as the military men, he exchanges insults with them.

In an onslaught of slurs, he accuses them of being Min Aung Hlaing’s guard dogs, and of being unfaithful to their country.

The soldiers respond with insults of their own. Cut off from the resupply of men and food, they stand their ground, firm in their belief that it is the military’s right – its destiny – to rule the country.

The ideological gulf between both sides is unbridgeable.

The carrot and stick approach continues for another 30 minutes or so, before the resistance fighters withdraw.

In his enthusiastic appeal for surrender Nay Myo Zin has inadvertently given away the men’s position (“I’m 400 yards away beside the loudspeakers,” he said), and they are worried about an artillery or mortar strike. Later that evening, the hillside takes a direct hit, without injuries.

This is more than just an ideological battle, it is a generational war. The young against the establishment, a new order fighting to break free from a tenacious old order. The connected versus a disconnected elite. The same youth who heard tales of failed revolutions and who have decided now is their time.

After half a century of military rule, Myanmar enjoyed a brief experiment with democracy starting in 2015 under Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy.

For many young people those years, though not without deep problems, marked an all-too-short golden age of freedom. The ballot box had failed them, then peaceful protest in the wake of the coup was met with killings and arrests. Many of those fighting told us there had been no alternative but to take up arms.

Thousands have abandoned studies and careers in major cities such as Yangon – doctors, mathematicians, martial arts fighters – and fled the cities to join established ethnic and resistance groups that had long opposed military rule.

On this front, all the fighters are under 25.

Nam Ree, a 22-year-old with the Karenni Nationalities Defence Force, KNDF, explains why he joined the resistance.

“The dogs [a commonly used insult for the military] have been unjust. They carried out an unlawful military coup. We, the youth, are discontented with it,” he says.

He is wearing flip flops, blue nail varnish, faded combat trousers and ammo belt across a Barcelona FC top. Unlike most of the men around him, he has a ballistic helmet. No-one has body armour.

The KNDF are a new force of young fighters and commanders which appeared after the coup. Ethnic armed groups have been fighting against the military in Karenni – also known as Kayah state – for decades. But the KNDF has brought them unity and battlefield success.

The tide turned against the junta on 27 October last year when an alliance of groups in the north of the country overran military positions and border crossings. Dozens more towns across the country have fallen since then into the hands of the armed opposition. The military still controls the main cities, but is losing control of the countryside and Myanmar’s borders.

The KNDF says it, and other insurgent groups, now control 90% of the Karenni state. It may be the smallest in the country but it has become a hardcore centre of resistance.

Under the shade of a mango orchard sits the powerfully built, tattooed KNDF deputy commander, Maui Pho Thaike. An environmentalist who studied in the United States, he first picked up a gun three years ago.

He doesn’t recognise the military junta as a government, it is the oppressor of the country’s many ethnic regions, he says.

He says the whole country is now fighting the army.

“The strategies are changing. All the attacks are now co-ordinated,” he says.

The KNDF has no lack of fighters, but ammunition and weapons are in desperately short supply. Mostly the insurgency is funded by donations from the country’s diaspora.

“We do have enough heart, we do have enough morale, we do have enough humanity. That’s the way we’re going to defeat them,” Maui says.

A tattoo on his hand reads “free thinker” – from another time, when Myanmar was briefly on its thwarted move to democracy. Are you still a free thinker, I ask him. “In this uniform, no,” he replies. “But without this uniform, I’m a free man. And that’s our dream. We’ll create it again.”

To enter Myanmar is to travel not just to a forgotten war, but to country severed from the outside world. Much of the mobile phone network, internet and electricity has been cut off in Karenni state. The military may be on the back foot but their remaining bases control the main roads through the state.

A 60km (37 mile) drive from Hpasang further north to the town of Demoso took more than 10 hours across rutted dirt tracks, over hills and through rivers and valleys.

We arrived to the aftermath of a failed assault on a military base in the nearby town of Moebye, in which 27 members of the resistance had been killed.

In a jungle hospital, young men from the KNDF lie on hospital beds on dirt floors. Some smile and give a thumbs up, most are missing limbs.

Aung Ngle, 23, has a horribly swollen left leg after taking shrapnel to his femoral artery in the attack on the base. He is too ill to talk, but as he begins to weep, three of his comrades come to him, holding and comforting him. They won’t be able to operate. He will have to make the long journey to Thailand for further treatment. I ask a doctor if he will survive. “He will be fine,” he says. “But right now I think he’s depressed because he can’t fight anymore.”

In many respects, this is a conflict from another age, brutal and intimate. The fighting in Moebye lasted for days, at close quarters, with uphill frontal infantry assaults on the military’s bunkers.

One man has multiple injuries to his hands, legs and stomach. They were caused by a hand grenade, he says. They had gone to retrieve a commander who had been hit in the leg when it came in. “It was at close range – about 30ft,” he says.

The war has a slow ferocity, as we saw for ourselves when we travelled further north into southern Shan state, towards the town of Hsihseng. Near there, a counter-offensive was underway as the military tried to capture the route to Loikaw, the state capital, which also remains contested.

It is not their state, but the KNDF is in the lead under the command of a fighter called Darthawr. He, like many of his men, has been injured in previous attacks and a dark red scar peeks out from under the arm of his T-shirt.

“Defending this place for us is like defending our home,” he tells me. He is in shorts and flip flops and neither he nor his men have body armour. Nor do we.

As we stand on a low hilltop by a banana grove, he points out the military’s positions, 1.5km (0.9 miles) away. Shells begin landing nearby and there is a scramble to some shallow trenches. The shells, likely mortars, keep coming in, getting closer. A sustained exchange of automatic gunfire can be heard at close range – it sounds like the soldiers are far closer than previously thought.

It quickly becomes apparent that a group of soldiers is making its way through a minefield to our position. We leave, driving at speed as the shelling continues, a mortar striking the road directly ahead of the vehicles.

“Their troops got injured, and that’s why they are randomly shooting everywhere,” Darthawr explained.

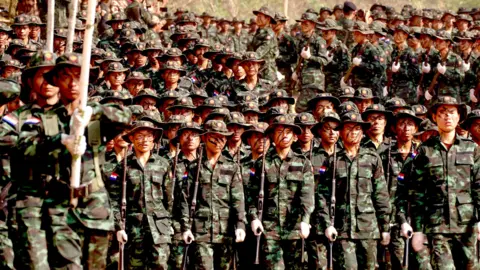

At a graduation ceremony on a baked-hard dirt parade ground cleared in the jungle, rank after rank of new recruits march past in formation. They salute the KNDF leadership, their rubber-soled canvas boots stamping up the dust. The young men and women – many just turned 18 – march to the beat of a song in English, “Warrior”. Its lyrics:

I am last to leave, but the first to go

Lord, make me dead before you make me old

I am a Soldier and I’m marching on

I am a warrior and this is my song

There are more than 500 – a record number of recruits. The ranks have been swollen after the junta, running short of men, enacted a conscription decree which sent young people in their hundreds fleeing to insurgent territory to join the revolutionary cause.

The last time I saw the troops, they were training with bamboo rifles. Now they have the real thing.

Their commander, Maui tells me that there isn’t much time for training. “Our strategy is like, we organised one month training, intensive training, then we go to fight.”

As the ceremony ends the mood is wild. A young rapper, MC Kayar Lay, who also graduated that day sends the fresh recruits into a frenzy of dancing and celebration.

It is difficult to predict where the uprising will lead. For both sides, this is an existential war and one increasingly marked by bloodshed and bitterness. There appears to be no going back.

After three and a half weeks, we were back in Hpasang. The army base, which had been about to be stormed by the resistance when I left, remained standing.

The military had tried to send in reinforcements – some 100 men – but in a battle with the insurgents, 57 were captured, the rest fled or were killed.

The army failed to resupply the base but the encounter with the opposition forces had another consequence. It meant armed revolutionaries’ ammunition was depleted – and they no longer were able mount an attack on the outpost.

The day before we arrived, army war planes had bombed the hilltop overlooking Hpasang, killing three of the young fighters we had met earlier, and injuring 10.

Before, there had been music and singing from their positions on the banks of the wide Salween River, an almost relaxed willingness to wait out their enemy.

But now the mood had darkened – more appeals for surrender seemed unlikely. It would now be a battle to the death.

Source: BBC